Your cart is currently empty!

Category: News Main

-

Dharavi: Rags to relief

By Preeti Pooja

The snapshots of filth and fantasy in the biggest slum of Asia – Dharavi is by now a much romanticized subject on celluloid to capture the wide canvas of a shantytown and the struggle, hope and hopelessness of its over one million residents.

Dharavi is home to vital unorganized industry workers, mostly children, who sift and collect 8.5 metric tons of filth, garbage, plastic, metal and scrap everyday.

Most of these rag pickers, come as migrants from every part of India. They often live in conditions worse than that in refugee camps. Many are malnourished. They are constantly exposed to hazardous toxins and diseases.

Their subhuman living conditions provides little access to basic education, sanitation, water, electricity and healthcare. Dharavi has severe problems with public health, due to inadequate toilet facilities, compounded by the infamous Mumbai flooding during the monsoons.

This is also a place where Mumbai’s underbelly of drug peddlers thrives. Low house rents and access to livelihood like rag picking has attracted minorities and the poorest of poor from different states to Dharavi. The economy here is based on recycling besides some pottery, textile factories and leather units. Dharavi is home to more than 15,000 single room factories.

But Dharavi is not just a haunt of film and documentary makers on a bounty hunt of poverty and filth as creative ingredients. Some NGOs have chosen to work here to better the living conditions of many of its uncared for residents.

Acorn Foundation (India) is one of them. The Acorn Foundation (India), which is affiliated to ACORN International, is supporting, Dharavi Project India. They are working to improve the lives of the rag picker community in Mumbai besides Delhi and Bangalore. Acorn is also doing extensive study on urban solid waste management in Mumbai and trying to implement actions to alleviate this issue.

Vinod Shetty, an advocate by profession, is actively involved with Acorn Foundation (India). Mr. Shetty narrates some of the heart-rending realities of life in Dharavi.

“Any big city survives on the services of rickshaw pullers, sweepers and rag pickers. It’s them who are at the bottom of the pyramid and ensure that the city keeps running. The society must acknowledge to the services of these people who live without any social security,” says Mr. Shetty.

Acorn firmly believes that this community of unorganized labourers is an invaluable human resource to the city.

“Mumbai would have been reduced to a dumping yard creating havoc with serious sanitary issues had there been no rag pickers who recover, recycle and ensure reuse of the waste,” he says.

ACORN, under the Dharavi Project, tries to organize this vulnerable section and train them in scientific methods of waste handling, segregation and recycling.

Currently there are 35 members of Dharavi Project working at different levels of recycling. Some of the initiatives taken by Acorn Foundation (India) are like providing informal schooling to the children. ACORN organizes health clinics, cultural programmes and workshops where the beneficiaries learn music, photography and arts.

Celebrity shows and concerts like BOxette are also a part of the initiative to bring a crumb of entertainment to the disadvantaged community. In a recent eco fair organized in the Maharashtra Nature Park, presence of celebrities like Katrina Kaif, Shankar Mahadevan and Suneeta Rao spiced up the event.

One of the most exciting programmes of the Acorn Foundation is in association with Mumbai’s popular nightspot Blue Frog. Musicians and celebrity rock bands conduct workshops for these children.

Recently the international BeatBox group, the Boxettes, (beatboxing is vocal percussion) held workshops for the children while the Sout Dandy Squad (Tamilian rappers) performed with several international artistes too.

“The purpose behind these events is clearly to showcase local artistes and give the youth of Dharavi a chance to witness international artistes up close which they never dreamt of. They bring cheer among these children, though short lived. The musical celebration is often themed with graffiti art and sculpture,” says Mr. Shetty.

Acorn has provided the members of the Dharavi Project with identity cards and recognition. They have formed their own committee to conduct waste awareness programmes.

“One programme is exclusive for children who are taught about waste management in primary schools. Under this programme students are given lessons on how to reduce and manage waste at home,” he says.

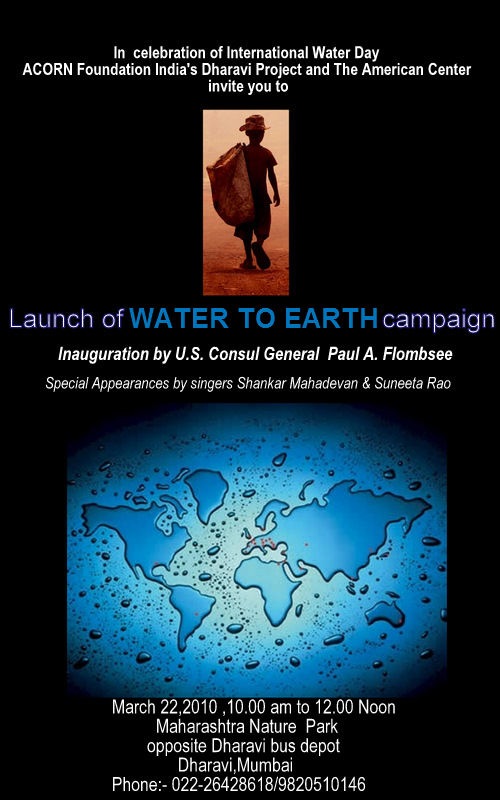

Besides entertainment, Acorn also organized multimedia campaigns on Water Day, highlighting issues of water conservation, water filtration and use of renewable energy sources.

Acorn Foundation (India) entrusts the faith within these rag pickers to make them feel a part of the society and live the life of a respectable citizen.

For details visit Acorn Foundation’s (India) Website: www.dharaviproject.org

-

Visit from the US Ambassador to India, Timothy J. Roemer

The US Ambassador to India, Timothy J. Roemer, and his wife Sally, visited our ACORN India ‘Dharavi Project’ on May 11, 2010. The US consul general in Mumbai, Paul Flomsbee, who has previously visited the project, was also present. Roemer was interested in seeing how the Dharavi rag-picker community contributes to the ecological well-being of the city, and how the Dharavi Project enhances their livelihood.

Roemer was given an overview of the Dharavi Project’s mission and activities, and then provided a tour of the non-profit’s newly-commissioned office and waste segregation center, a paper recycling facility, and the massive waste collection area nearby. During the visit, Roemer personally interacted with rag-picker members and recyclers, as seen in the first picture below, and even played a quick round of cricket with rag-pickers kids while balancing on one of the massive pipelines leading out of the city. Two members of the rag-picker community, Rafique and Lakshmi, shown in the third picture below, described their work to Roemer. Finally, Roemer tried his hand at one of the paper recycling machines.

Roemer learned about how the Dharavi Project program in Mumbai organizes 400 or so rag-picker members, gives them identification, and runs relevant waste management and cultural programs with 30+ schools, artists and even some corporates. The Dharavi Project also works closely with the American School of Bombay on a ‘waste matters’ campaign that helps the school kids manage their waste and donate a portion of it to the rag-pickers. Roemer expressed his support for a similar program with the new US consulate facility in Bandra Kulra Complex.

-

Giving ragpickers the fourth R

By: The Times of India

They comprise the 1,20,000-strong army that saves Mumbai from further environmental degradation. Yes, their livelihood is dependent on the 8,000 tonnes of waste that the megapolis spews out daily. But if it weren’t for their recovering, recycling and ensuring reuse of the waste (the three Rs of their difficult lives), this city would have been one big dumpyard.

Ragpickers’ working hours are spent in combing the city’s alleys, beaches, rubbish dumps and even diving into the foetid waters of mangrove swamps. Eventually they congregate at Dharavi, the world’s largest recycling unit where almost 80 per cent of dry waste is reused.

Now there’s an initiative afoot to bestow a fourth R on the ragpicker brigade—respect. The Acorn Foundation India Trust is set to organise these workers and train them in scientific methods of waste handling, segregation and recycling. “We want to highlight their work in protection of the environment,” says Vinod Shetty of the Acorn Foundation. “We want the government to set up a board whereby polluters pay a cess of about one per cent which can go towards giving these ragpickers a proper income with safe equipment like gloves and other amenities. We want them to be trained in how to handle toxic waste and expertise in recycling goods in a non-hazardous way.”

For a start, all members of the Dharavi Project are being given identity cards. They have formed their own committee which is involved in waste awareness programmes. In one programme, young ragpickers are partnering with schools in waste management. Currently there are some 350 members of the Dharavi Project.

The foundation has also undertaken another initiative— to organise health clinics, programmes and workshops from which young children engaged in ragpicking can get some kind of informal education in music, photography and other arts. A number of artistes have participated in such programmes, among them singers Shankar Mahadevan, Sunita Rao and Apache Indian and Katrina Kaif. “Nearly 40 per cent of those in the waste business are children and women,” says Shetty. “We do not want to support child labour but realise that this sector needs alternatives. We hope such cultural events will help them think differently.”

-

Garbage is not a dirty word

With the help of kids, Vinod Shetty is getting the city to show some respect to rag pickers, reports Kevin Lobo

Dharavi, Asia’s largest slum, is the last place you’d associate with environmental conservation. But as the world celebrates Earth Day today, Vinod Shetty, founder of NGO Acorn India, is out to prove how the rag pickers of Dharavi are one of the main cogs in the wheel for recycling the city’s daily output of 10,000 tons of waste. With the help of about 450 kids, a sizeable amountof whom are rag pickers, Vinod plans to change the perception of this city.

These kids will paint together, make paper bags together, and watch documentaries together. To add star value to the event, Shankar Mahadevan will lend some glitter. The highlight of the day will be the sight of kids from diametrically opposite backgrounds grooving together to music by Ankur Tewari and Something Relevant.

But change does not happen overnight. Vinod runs a waste management programme in 35 schools in the city. “The same kids who have been trained to think that the kachra dabba is dirty take pride in joining the waste management committee,” says Vinod.

The 40-something advocate has been running this programme for the past two years to educate kids about the plight of these green-collar workers. “We were trying to get the BMC to clean the waterfront at the Bandra Bandstand. One lazy evening at my house in Chimbai village, there was this group of people cleaning the place up for free. There was no media, no cameras around, just three to four rag pickers gathering up plastic,” says Vinod.

Facilitating a change of perception was the first thing that struck him. “When a person is living a corrupt life, you can’t tell them that they are corrupt and expect them to change. You have to change people before they become corrupt,” he explains. Kids were his natural target audience.

Though his school programmes have educated kids, both about rag pickers and the benefits of recycling waste, if perceptions have to change there is nothing better than face-to-face conversations. Thus came about the Earth Day event.

With Earth Day falling just after the school exams it has been difficult to get kids to attend the day-long programme. Vinod is also severely shortstaffed. With just one person on the pay roll Vinod depends heavily on volunteers to get things done. But over his 20-year ‘career’ in social work Vinod knows the drill.

A change in attitude is not all he is gunning for. Vinod does feel rotten that these kids don’t have a chance to go to school but feels that even that will change with perception. If there were systems in place, where garbage could be segregated into wet and dry waste, that would be a start. Money can be generated through recycled products which in turn could be used to establish schools.

“Since rag pickers don’t use the AC, nor drink mineral water, nor drive SUVs, the environmental problem is ours, not theirs. We are trying to create an interactive bond between the rag pickers and school students. I want to protect their livelihood. Instead of burning waste we can start taking things to recyclers, with rag pickers leading the way,” he says. -

Slums as self-confrontation

ACORN International focuses on organizing slumdwellers in India. The following essay by Ashi Nandi is an interesting discussion of the overall issues much on people’s minds in India as slum removal is a bitter, though often cosmetic, issue in advance of the 2010 Commonwealth Games in Delhi.

By Ashis Nandy

The attempt to free cities of slums will only make them invisible.

There is another way of looking at slums, which is not only more creative but also more compassionate and humanitarian. Slums are parts of the city that constantly reminds us of our moral and social obligations. They are reminders that another India exists. People loathe slums not just because of the poverty they display, not just because the slums embarrass them in front of foreign visitors, but also because the slums look to them like indicators of their backwardness and do not allow them to forget or deny the poverty and the exploitation on which their prosperity is built. They blow up Rs 40,000 for a dinner for four persons at a five-star hotel while people scavenge for food outside the hotel. The slums are reminders of the open wounds of a city. That reminder is painful. Many do not want such reminders to be there.

Many see slums as failed parts of cities. They are regarded as parts of a city that do not conform to ruling ideas of an ideal city held by people in other parts of the city.

There have been some changes in the way people have looked at slums ever since colonial cities emerged. At one time, slums were seen as a kind of an invisible city: a place where servants and the poor blue collar workers stayed and one did not have to care for them. The architect-activist Jai Sen had a term for this attitude: in an essay in the journalSeminar he called a slum an Unintended City. There was little or no genuine attempt to accept the poor and disadvantaged as part of the city’s future—to accept them as equal and integral citizens or to re-plan the city according to their needs—Sen wrote

I think things have changed in the three decades since Sen said this.

Slums are not just the unintended city. They are now regarded parts of the city that should not be visible. City authorities in Delhi and Mumbai are planning to cover up slums for the Commonwealth Games. They are an embarrassment, which foreign visitors to the city must not see. A slum is a part of the city that has no business to be there.

Then there is the political-economic perspective on slums: people with low earnings prefer to stay in slums because they are close to their places of work. So the rich and middle classes get their cheap labour—drivers, vegetable vendors, domestic helps—from the slums. This approach has a built-in contradiction. The upper and middle classes do not want to pay their domestic helps at First World rates, but they want slums eliminated as in some First World cities, or in Asian cities pretending to be First-World cities like Singapore and Hong Kong. They will not do what citizens of Singapore and Hong Kong have done to eliminate slums. In Singapore and Hong Kong, too, you have to pay through your nose to get a domestic help or a chauffeur.

Slums are not regarded as political issues in many countries. But that is not so in India. Here, elections still reflect some of our real issues. You are always afraid when you see slums: it reminds the middle class they are sitting on a volcano. The fact that our political system has not forgotten the slums makes the wealthy and the middle class nervous.

Such anxieties have cultural consequences. In fact, I would go to the extent of saying that in the West, the more interesting cities have slums. New York has slums; Houston does not, not at least visibly. Los Angeles does not have conspicuous slums, Washington has and it’s a more interesting city because of that. The contradictions of the city are in full display. A society’s creativity depends on the oscillation and dialogue between slums and the rest of the city.

New York is an intellectually rich city because it has many things that are going out of fashion in mainstream America, such as street life and street food, street graffiti, street-side artists and musicians. It also has crime, sleaze and drugs. The latter have an effect somewhat similar to that of the activities of the Naxalites or the Maoists: they remind the middle classes and rich sections of a large number of disposable people living at the margins of desperation. In New York, the capital of global capitalism, more than 40,000 homeless adults live in streets, subways, and under bridges and train tunnels of the city; and 25 per cent of all children live in families with incomes below the official poverty line. New York is New York because it has, to some extent, learnt to live with slums. Many other cities in the West have dismantled slums but not homelessness.

Slums highlight such contradictions. If you have disowned parts of yourself and built up an elaborate system of psychological defenses, the contradictions do not vanish. They remain and you feel you are always being held accountable, being accused—by yourself. Such contradictions sharpen creativity. They impinge on the writers, artists and thinkers. The finest Dalit poetry in India, for example, has come not from writers in rural India where the situation may be more oppressive for the Dalits or from Dalits who have made it, but from writers living at the margins of society. They have lived either in a slum or close to it

This is not an attempt to romanticize slums but to emphasize that the slums are often the only connection the urban middle class has with some of the grim realities of society. The well-known Bangladeshi economist Mohammad Yunus once said that the only time the country’s rich and the wealthy faced what the poor in the country’s villages had lived with for centuries was when floods came to Dhaka. Likewise, the slums create a certain awareness, which we can afford to ignore at great risk. If we remove slums, the only people in touch with that reality may well be the Naxals, the Gandhians and some of the much-maligned, politically-aware NGOs.

Town planners in many countries think slums can be replaced with low-cost housing. Low-cost housing has relevance but it is neither foolproof nor offers a long-term solution. Once you give people such houses some of them might sell them to developers for gentrification and, ultimately, the other city encroaches on such projects. People who had some protection in slums, at least had a roof on their heads, lose that protection. Low-cost housing might lead to American-style gentrification in our political economy, too.

Even by conservative estimates, one-fourth of India is poor. They cannot be ignored. In our political system, electoral pressures and vote banks matter. And empowerment can be a solution. It is working in the case of the Dalits. It can bring small reliefs such as better sanitation, cleaner water, minimal healthcare and more toilets. Even now, without such facilities, lots of people prefer to stay in slums; they try to make something beautiful out of whatever little they have. Human beings are a resilient species and many prefer to live in a place where such resilience is in full display. The well-known Hindi film director Manmohan Desai used to stay in a locality that could be classified as a glorified slum. So did Vinod Kambli, the famous cricketer. Harlem has even become fashionable; former President Clinton has an office there now. Slums are not infra-human.

Planning cannot eliminate slums. As long as there is large-scale deprivation, as long as our rulers, our media and our urban middle class believe that proletarianization is better than being a farmer, artisan or a tribal, there will be sizeable number of people who will be made available for blue-collar work in our cities. Such people will like to stay close to their places of work. If you upgrade or destroy one slum, others will come up in its place a few hundred feet away.

The recent attempts to free Indian cities of slums will merely make the slums less visible. This is not a new project. Sanjay Gandhi tried it. Jagmohan tried it. I don’t blame them any more in retrospect. The urge to make slums invisible is there in almost every unthinking Indian—not just in the powerful, the foolish and the heartless.

The desire to secure services from slums and yet not see them is one of the diseases of our times that is taking an epidemic form.

A sociologist and a clinical psychologist, Ashis Nandy is with the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi

-

CNN interviews Vinod Shetty of Acorn India / COI

CNN Mallika Kapur looks at how India is trying to dispose waste.

-

Right to Education for the Disabled

ACORN India in Bangalore organized a Kalajatha (Street Play) to create awareness on

ACORN India in Bangalore organized a Kalajatha (Street Play) to create awareness on

right to education for the disabled in our working areas. The Kalajatha was organized by ACORN and supported by SN Basaveshwara Education Trust and the Acharya Institute of Management Studies. The Kalajatha was held in five slums of Bangalore where ACORN has members. The Kalajatha was held on 12th and 13th of March.On 12th the Kalajatha was held in Binnamangala and MV Garden. On 13th the Kalajatha was held in Lingarajapuram, Rajiv gandhi Colony and Devarjeevanahalli.

The Students of AIMS supported by acting in the plays and SN

Basaveshwara Education Trust supported by providing the sound system

and the vehicle was supported by the BBMP. -

ACORN en Honduras

Los representantes de ACORN Internacional Chef Organizer Wade Rathke y la cabeza organizadora de Mexico ACORN, Suyapa Amador, recientemente gastaron cinco días en reuniones con activistas, sindicatos, políticos, profesores y organizaciones comunales de Honduras, valorando el interés en ACORN International y asistiendo en el desarrollo de una nueva afiliada Honduras ACORN en ese pais. Excelentes reuniones fueron sostenidas en San Pedro Sula y poblaciones alrededor, Marcala en La Paz, y en la ciudad capital, Tegucigalpa.

Los representantes de ACORN Internacional Chef Organizer Wade Rathke y la cabeza organizadora de Mexico ACORN, Suyapa Amador, recientemente gastaron cinco días en reuniones con activistas, sindicatos, políticos, profesores y organizaciones comunales de Honduras, valorando el interés en ACORN International y asistiendo en el desarrollo de una nueva afiliada Honduras ACORN en ese pais. Excelentes reuniones fueron sostenidas en San Pedro Sula y poblaciones alrededor, Marcala en La Paz, y en la ciudad capital, Tegucigalpa.La respuesta fue entusiasmadora. Parte de la razón de esta respuesta esta ligada a las necesidades insatisfechas históricamente, a insolubles problemas de injusticia e inadecuados servicios básicos. La población volvió a quejarse acerca del agua, de la vivienda y de las respuestas a seguridad social básica. La otra razón del interés esta claramente ligada a la insatisfacción con la cúpula militar del ultimo año, la cual desplazo un presidente elegido, aun popular, con mucho trabajo y un moderado ingreso comunitario. La necesidad por un cambio fue acentuada por todos estos eventos provocando un más profundo interés en construir una organización comunitaria.

Prometimos hacer lo que podemos para responder identificando organizadores potenciales de Honduras que podrían ser contratados y entrenados en nuestro modelo organizacional. Si todo va bien, esperamos que ellos puedan estar listos para comenzar a manejar la organización y abrir operaciones de Honduras ACORN en San Pedro Sula y Tegucigalpa a fines de la primavera o a comienzos del verano.

También nos reunimos y disfrutamos la hospitalidad de los líderes y empleados del café de las mujeres y del cultivo de la sábila y de las cooperativas de mercadeo, COMUCAP en Marcala. Nos hemos comprometido a trabajar como socios con ellos en la búsqueda de nuevos mercados para sus productos en los países de Norte América: Canadá, Méjico y los Estados Unidos.