Your cart is currently empty!

Day: March 23, 2011

-

The Sum Of All Parts

Artefacting Dharavi kids do an Anish Kapoor

spotlight: dharavi

Artistes of the world are converging on a much-bemused Dharavi

Dharavi In Fashion

TV shows Slumdog Secret Millionaire and Kevin McCloud: Slumming It on Channel 4, The Real Slumdogs on Nat Geo; documentary on Discovery Channel; another on human drug trials in Dharavi by Al Jazeera TV and a third on the area’s recycling units by Sky News

Independent films: Dharavi: Slum for Sale, directed by Lutz Konermann, Canadian film Slum of Millionaires; audio-visual series on Dharavi by Richa Hushing

Online projects dharavi.blogspot.com and dharavi.org

Books Dharavi: Documenting Informalities, ed. Jonathan Habib Engqvist and Maria Lantz; Dharavi Anthlogy (forthcoming) by HarperCollins, compiled by Joseph Campana

Exhibitions ‘Artefacting Mumbai’, a 3-month artistic exploration of Dharavi; ‘Places We Live’, a multimedia exhibition by Norwegian photographer Jonas Bendiksen

Tours Reality Tours, Be the Local

***

When well-heeled Mumbaikars stride into Dharavi, you know something odd is afoot. And sure enough, there they were on a January morning to take in the “buzz” generated by Artefacting Mumbai, Dharavi’s first “art residency”, for which artist Alex Mazarella White, videographer Casey Nolan and photographer Arne de Knegt had “immersed” themselves in Dharavi for three months. Given the language barrier and their lack of engagement with the locals, the trio’s “artistic interventions” had left Dharavians feeling rattled. They wondered why these “foreigners” had made gigantic murals (“Christian paintings?” they asked), why their own mugshots were up on large posters; why their children had been made to pelt a tin sheet with dripping red wax that got their clothes awfully messed up (apparently to recreate Anish Kapoor’s Shooting Into a Corner installation!). But for the chic Mumbaikars chattering excitedly as they viewed the artwork in Dharavi’s snaking alleyways, none of that was particularly relevant. Nor the fact that the huge multicoloured ‘Welcome’ sign greeting them was painted by outsiders, not Dharavians.

Welcome, indeed, to the new Dharavi, dismissed for years as an eyesore but now the muse of artists, writers, filmmakers and academicians. Two reasons shape this meteoric rise of Mumbai’s, and India’s, biggest slum in popular consciousness. The first, and obvious one, is Slumdog Millionaire, the urban fairytale that exoticised its garbage piles and bustling alleyways, and went on to trigger a flood of documentaries capturing the “real Dharavi”. Since the movie hit Oscar glory in 2009, film crews from Discovery, Nat Geo and BBC’s Channel Four have come and gone. With real-time “casting” by the likes of Dharavi resident Rajesh Prabhakar, who earns between 250 and 300 dollars a day finding “characters” in his neighbourhood—from ragpickers to super-rich entrepreneurs to rap singers—they are able to wrap up their shoots fast, and go back with a made-in-Dharavi tale.

The second, more subtle reason for Dharavi’s new, “hip” turn is that it’s the ‘ideal’ slum, and one threatened by redevelopment to boot, at a time when urbanists across the world are looking at slums with new respect as industrious, dynamic, sustainable, eco-friendly urban settlements. That Dharavi, home to about a million people from all over India, sits bang in the middle of the city, flanked by five train stations, only adds to its allure.

More than one Dharavi-trawler, camera in hand, is well-versed in ‘slum aesthetics’, a term that has found its niche in cinematic idiom and popular culture in the last decade. “Slums are used as dramatic backdrops to tell stories like in City of God or District 9,” says Mathias Echanove, founding member of Urbz, an organisation that works on alternate ideas of urban development. While City of God was set in the favelas or slums of Rio de Janeiro, a film called Tsotsi, set in Johannesburg’s Soweto slum, won the 2006 Oscar for Best Foreign Language film. And so, while Rio now has favela tours, Dharavi has Reality Tours and Be the Local tours, plus an unending stream of foreign researchers, architects, planners, design students, artists, musicians and photographers from across the world making their way here to see, observe, research, write and conduct workshops. Their route into Dharavi is usually via organisations like Urbz and SPARC (Society for the Promotion of Area Resource Centres), who make no secret of their passion for Dharavi, through essays, cultural and design workshops and websites like dharavi.org and urbz.net.

But how do locals themselves react to seeing their own lives repeatedly documented via art, design and research? At least some are openly sceptical. Bhau Korde, now over 70 years old, is dismissive of “intellectuals” who love to comment on Dharavi without really engaging with it. “On any day, at any hour, there are at least 10 foreigners walking around with cameras. Most are interested in only capturing the poverty of the place,” he says sardonically. Anjum, another resident, is just as cynical. “The numbers of visitors have shot up in the last two years. Most of us just ignore them and carry on with our work,” he shrugs.

Richa Hushing, an independent filmmaker who made a series of short films on Dharavi’s communities, admits to hearing a common complaint here. “They say, ‘you come with your cameras, make films but we never know for what’,” she says. It made her think, and eventually decide, to screen films, her own and those of others on Dharavi, for residents. Similarly, Lutz Konermann also screened his documentary Dharavi: Slum for Sale in Dharavi, attracting strong reactions, both positive and negative, from residents since it dealt with a subject uppermost in their minds—redevelopment.

Dharavi’s children, the most favoured subjects of photo essays on the place, have come up with their own unique reaction to the invasion of visitors. “They want to take pictures too. They want to play at becoming surveywallahs and photographers,” says artist Himanshu S., who interacts with the kids who come to The Shelter, supported by Urbz, for art and other classes. This has had a positive spin-off. The children were able to document their neighbourhood like no outsider could, and their photographs, priced at between Rs 1,000 and Rs 1,500, were exhibited at the Kala Ghoda Festival, held this February. Only two were sold, but the exhibition did attract volunteers eager to work in Dharavi.

Such engagement is exactly what Vinod Shetty of Acorn Foundation, which works with Dharavi’s ragpicker community, is aiming for too, despite fumbles like Artefacting Mumbai. He has tied up with a theatre director to create a play with Dharavi’s children. They will pen the dialogues and also act in the play, portraying their realities. Blue Frog, the hip “live music” club, has also become an unlikely entrant into Dharavi’s world—its visiting foreign artistes hold music workshops for Dharavi’s kids through Acorn.

Not all such interventions are sustained and it’s this lack of consistency that feeds the scepticism of Dharavians like Bhau Korde. The photography workshops are sporadic, and as Emanuelle de Decker of Blue Frog herself admits, some older kids question the point of music workshops that let them “have fun for just a day where they get to perform with the artiste”. She rues how there’s “always a long wait for the next interested artiste”.

How great a cultural interaction can be, when it actually works, is encapsulated by the experiences of HeRa aka Netarpal Singh in Dharavi. This hip-hop dancer, who grew up in the ghettos of Queens, New York, visited Dharavi to see French graffiti artists work. Spontaneously, he began B-boying, an acrobatic version of hip-hop dancing, and was soon joined by enthusiastic Dharavi kids. “Hip hop came naturally to them. It connects us people from the street, in South Africa, Korea, Palestine, the US and India,” says HeRa, who was so charged with this encounter that he decided to start a hip-hop centre, Tiny Drops, on the slum’s outskirts. Now Dharavi kids like Akash, Rashid and Faizal come here whenever they can, practising for hours to get their moves right. On discovering that the kids he was teaching hated the term “slum dog”, he turned it around, starting an artists’ collective called Slumgods with his Indian-American rapper friend Mandeep Sethi and Dharavi’s dancers. “It makes these kids redefine their identity by connecting to an international hip hop culture. They become empowered,” he says. Creative or jarring, sincere or exploitative, loved or hated, there is no doubt about one thing: the invaders are changing Dharavi.

-

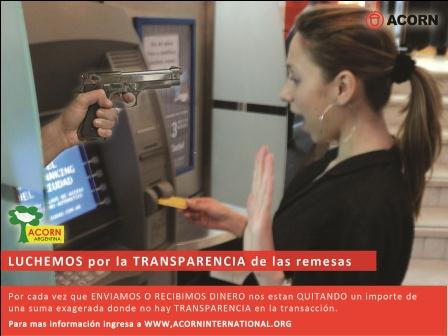

Remittance Justice graphic

This powerful Remittance Justice graphic was done by Uriel Brodsky.