Your cart is currently empty!

Blog

-

Difundiendo información en Lima- Spreading the word in Lima

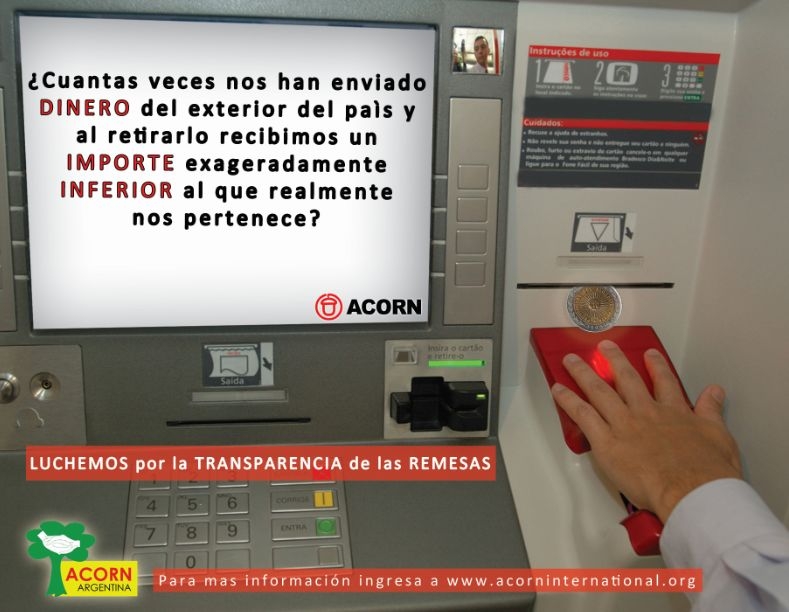

Líderes y miembros de ACORN Peru difunden la palabra en Lima por el alto costo de las remesas.

ACORN Peru leaders and members spread the word in Lima about the high cost of remittances.

-

Informe sobre Remesas – Peru Remittance Report

En Lima, Perú estamos siguiendo la Campaña de Remesas con acciones abiertas a la población en general, para insertar miembros a la organización de diferentes ámbitos y localidades, ya que en las Comunidades donde trabajamos actualmente difícilmente podemos encontrar miembros que reciban envíos de remesas del extranjero. Las familias que la componen, por su bajo nivel de ingresos, no pueden acceder o aspirar a salir fuera del país y menos a trabajar fuera de él, por no contar con visas y recursos para poder pagar sus boletos al extranjero.

Es por eso que Nuestras Acciones consisten en salir a las calles y volantear para invitar a las personas a ser parte de ACORN Peru y unirnos para conseguir el objetivo Principal:

CONCIENTIZAR A INSTITUCIONES FINANCIERAS EN EL COBRO JUSTO DE REMESAS.

Las Actividades realizadas,

Entrega de Cartas a las entidades Bancarias; de las que estamos esperando respuestas

Volanteo alrededor de los bancos para identificar y motivar a aquellas personas que se identifiquen con la Campaña, para que se afilien a ACORN Peru.

(En los volantes, están los números telefónicos de ACORN. Próximamente esperamos contar con una cuenta electrónica exclusiva para la afiliación de estos miembros, a su vez que podríamos contar que ellos debiten. Según mi apreciación estas personas si contarían con una cuenta o tarjeta bancaria para sostener esta Campaña, a diferencia del miembro Común de ACORN en Perú.

Adjunto,

Fotos para que se hagan una idea de cómo estamos desarrollando esta Campaña.

In Lima, Peru. We are following the campaign of remittances, with actions open to the general population, to insert members into the organization of different areas and localities, as in the communities where we currently can hardly find members receiving shipments and remittances from abroad. Since the families that make up for its low income level does not aspire to reach or leave the country and less to work out of it, for not having visas and resources to pay for their tickets abroad. That is why our actions are to take to the streets and leaflets to invite people to be part of ACORN and unite to achieve the main objective. Sensitize FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS IN THE COLLECTION OF REMITTANCES FAIR.

Based Activities, Delivery of letters to banks, of which we are waiting for answers Leafleting around the bank to identify and motivate those who identify with the campaign, to join ACORN.

(In the leaflets, are the phone numbers of ACORN, Soon we hope to have an exclusive email account for the affiliation of these members, in turn we could count them and debited), According to my assessment of these people if they would have a account or credit card to support this campaign, unlike the common member of ACORN in Peru.Deputy photos to give you an idea of how we are developing this

Campaign. -

Wells Fargo response

BMO Financial ResponseView more documents from ACORN International. -

BMO Response

BMO Financial ResponseView more documents from ACORN International. -

La Matanza

La Matanza, barrio y limpieza.

La Matanza neighborhood and cleanup.

-

Community Development Committee Meeting

Below are the minutes from the Community Development Committee Meeting held on September 13, 2010

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE

MEETING (CDC)

DATE September 13 2010

VENUE Christ Devine Church KB

TIME 2.30 PM

Introduction

Community Development Committee (CDC) is an initiative of an organization called Concern World.It facilitated the formation of a fifteen member committee in all the villages in Korogocho.Each village committee was mandated to select and prioritize issues in their areas for a common action.

They were encouraged to source out for any technical and financial support on their own and were advised to be meeting once per months to deliberate on their issues.

All villages in their prioritized issues indicated education as one of the key areas of their focus and in fact to majority of them this was the starting point in their mid term goals. The CDC committee of KA through CONCERN invited committee members from other villages to come and share ideas on how they are tackling the education issue. They had identified ACORN Kenya Trust as a potential partner to work with and were to facilitate the forum whose main agenda was campaigns on education.

The process

The meeting started at 2.30pm with a word of prayer said by one of the CDC members from KA.

Mr. Kairu who is also the Chairman of that area made an opening remark and took members through the agenda of the day which was ‘education campaign’.

He also welcomed Mr.Owino the area chief who was present in the meeting to give his remarks. The chief assured all the members present of his knowledge about the meeting however, he informed the participants that he will not be for the discussion because he was handling some other visitors in the office. He also informed participants that Madam Chief could not attend the meeting as she was recapturing from an operation of a broken limb in the hospital. He encouraged members of Korogocho to continue with such meetings meant for development and officially declared the forum open before leaving together with RC Chairman who was also mourning the death of his Sisters’ child.

Attendance

- All villages had sent more than eight representatives with the exception of Gragon A which had two representatives and Gragon B that had no single representatives.

- CONCIRN representatives confirmed their attendance but would come late.

- Two community organizers from ACORN Kenya Trust were in attendance.

ACORN Kenya Trust

It was prudent for the organization to introduce itself as way of levelling of as a facilitator of the forum.

David Musungu took members through a brief profile of the organization.

ACORN is an Association of Community organization for Reforms Now. It is a new model of organizing adapted from America. It organizes community in the low and middle income areas for social, economic and political empowerment. The organization was founded in America forty three years ago by its chief organizer Mr.Wade Rathke and currently has branches in other counties like Canada, Peru, Argentina, Dominican Republic, India and now in Kenya where rolled out its programmes in 2009 in the two villages of Highridge and Kisumu Ndogo.

Myriad of issues were identified through caucuses, meetings and other dialoguing forums. Some of these were,

- Insecurity

- Environmental issues

- Water and sanitation

- Extreme poverty

- Health

- Education

- Youth issues

- Women issues

However education, health and sanitation were prioritized in that order.

ACORN intends to carry out campaigns on these issues’

Education campaign strategy of Acorn

Sammy Ndirangu took members through this item.

Education as an issue was given a priority as it is interrelated to all other issues highlighted above.

There is a big gap between the transitions from primary school and secondary school. About 10% of students who sit for the primary education examination are able to make it to the next level but the rest who constitutes the lager number no one who knows what happens to them. Others who make it to the secondary school end up dropping out of the school before even sitting for their form exams due to inability to meet the school fees and other basic requirements.

As all this happens, there are funds from the government devolved kitty in form of bursary fund which is supposed to assist these poor families for their children to access secondary education and tertiary collages such as CDF, LASDAP and ministry of education bursary fund. Very few pupils’ from Korogocho if any who have been able to benefit from the kitty and members of the community claims that this has not been in a smooth way. There are claims that the few who get it had do bribe or get it after a long and tedious process. The Question of where the rest of the funds go remains still a mystery to many of the residents.

Mr. Sammy said that Korogocho as a community has a right to these monies and its accountability.

The availability of a polytechnic in the area was also questionable. Majority of members do not know of its existence.

The government in it budget of 2009-2010 made a commitment to support these institutions. Students within these institutions are also being offered in form of bursary an average kshs.15, 000 per year for their training. Very few of community members know about this information which is critical for their own development.

It is in this line that Acorn Kenya is launching its campaign on matters of Education in the area. However ACORN Kenya can not win this campaign alone, the two villages of Highridge and Kisumu Ndogo can never win this campaign alone. It requires a concerted effort from all of Korogocho residents and other actors working in the area of education.

To succeed more facts are required, like the number of students not going to school, the number of those in school but can not access the funds and the real cases of studies of parents and guardians who have straggled to access the bursary fund but in vein.

Challenges

Members of the CDC were convinced that education was indeed a thorny issue in Korogocho and needed to journey together as a community to campaign and streamline the sector.

Peoples mind were however destructed when;

- A few members from the committee of Kisumu Ndogo engaged in petty issues within their ACORN committee.

- Same members did not understand the level of involvement of ACORN in the whole process of CDC.

- Other members claimed to have been given a different agenda on their invitation.

- Still others were expecting for some payments of money from CONCERN.

These led to some members matching out in protest.

Way forward

It was agreed that ACORN approaches individual CDC from every village and agree on how and when to convene for village level meetings first. This will then culminate to an area wide meeting for the same campaigns.

This idea was supported by the members of CONCERN who came in later and who also promised to do the follow-up as to why these CDC leaders behaved in this manner.

The meeting ended with a word of prayer at 4.20pm.

Minutes compiled by CO Acorn –Kenya

Cc. to Cos Redeemed Church

Cc. to the area Chief Mr. Owino